Our mission at National Braille Press is to put braille into the hands of blind children and adults to help them live their best lives. The Faces of Braille is a portrait project that tells the story of 10 of these braille readers, ranging from 4 years old to 94 years old, who use braille at home, work, and everywhere in between.

Meet Paul Parravano

Paul Parravano became blind at the age of three due to retinal cancer. His parents taught him braille, and it has made his work and education possible. Parravano is the co-director of Government and Community Relations at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Without braille, he couldn’t take notes or retrieve the information he needs to in order to do his job. Parravano’s local engagement includes scientific communities and disability rights communities, among other causes. An avid braille reader, he has served as a trustee of the National Braille press for almost two decades, and keeps up with the latest technologies for the blind and visually impaired.

“In my view, there is no substitute for braille, when maintaining a busy hectic calendar, or quickly and accurately accessing key pieces of data that I might need throughout the day. Whether for work, pleasure or family life, keeping braille close to me is critical for maximum independence and freedom.”

Meet Laura Wolk

“The thing I love most about braille is it allows me to have silence. We live in such a noisy world and it allows me to sit in the sun and read a book and you need to get away from the constant sounds of life, and there’s no way to capture that in other forms of technology."

Laura Wolk learned to read braille when she was three years old and has loved it ever since. Though she studied psychology for her undergrad, a conference at Notre Dame changed her life and led her to study law. Wolk is passionate about disability rights, and the more specific fields of discrimination including end-of-life care, the beginning of life, and how parents are informed if their child is disabled. She experienced the medical community encouraging terminating a pregnancy upon finding that the child is disabled, and she is driven to end that stigma. Wolk became the first female braille reader to clerk in the Supreme Court of the United States as a Law Clerk to Justice Clarence Thomas. Wolk’s hire has led to significant accessibility changes in the Supreme Court, allowing her to work there, which started a year before Wolk was scheduled to start.

Meet Benny Soriano

The Soriano family lives in Chicago, IL, where they each learn braille together. Their youngest, Benny, was born with Norrie, a genetic disease that causes congenital blindness and progressive hearing loss. Parents, Rebecca and Jeremy, daughter Olivia (14), and son Benny (4) are adventurous; they love visits to the mall, zoo, or concerts. Benny learns braille at school and has a Perkins Brailler at home, but the whole family is in on learning braille. They have braille labels all around their house and point out to Benny whenever there are braille signs when they go out of the house. Since Benny is so young, they’re able to learn braille at the same level.

“Braille is an amazing communication tool that we are learning, and it’s important to us to widen its accessibility in our world. Because it’s Benny’s world too. Our son deserves each and every resource out there to live his best life.”

Meet Larry Haile

Larry Haile has always loved to travel. Braille has helped him navigate. Haile struggled when taking the train abroad because there weren’t stop announcements to help him find where he needed to exit. He developed a strip map with braille to help him use the metro in Mexico City, Belgium, and Spain. Haile also uses braille to read novels while on his travels, as well as find his hotels, read playbills at the theater, and more. Haile is a volunteer coordinator (soon to be trainer) for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts at the Soldiers’ Home in Chelsea. He also provides assistive technology training and instructs blind students on employment readiness skills at the Perkins School for the Blind.

“Braille enhances my independence and contributes to me feeling as though I’m a part of the fabric of the community.”

Meet Donald Morrow

Donald Morrow lost his vision due to a propeller accident when he was 17. He learned braille soon after and pivoted his career into the fields of rehabilitation of the disabled and public welfare. Braille helped him earn his degrees, and take notes for his jobs. He learned to take notes in braille as quickly as sighted people. Morrow, now 94 years old and 29 years retired, is just months older than the National Braille Press. He continues to read braille magazines on science and technology from the Library of Congress and listens to talking books often. Morrow, impressed by advancements in assistive technology for the blind, often says if he had gone blind as a teenager in today’s world, he probably could have lived his career ambition of becoming an aeronautical engineer.

“Braille and volunteer readers kept me in touch with the world.”

![Chinonyerem Enwereji (Noye) is striking in a blue and white dress against a green background of foliage on a sunny day. She’s holding a bright blue Perkins Brailler “customized” with a Stitch sticker on it from the movie Lilo and Stitch, and has a bright smile on her face.] Chinonyerem Enwereji (Noye) is striking in a blue and white dress against a green background of foliage on a sunny day. She’s holding a bright blue Perkins Brailler “customized” with a Stitch sticker on it from the movie Lilo and Stitch, and has a bright smile on her face.]](https://info.nbp.org/hubfs/Noye_f_3348_1-1.jpg)

Meet Chinonyerem Enwereji

Chinonyerem Enwereji was born with albinism, and because of that, her eyes fatigue easily. She is legally blind and reading print has always been uncomfortable due to the fatigue. When she was nine years old, she quite literally took matters into her own hands. Enwereji taught herself to read braille, and as soon as the next year she was teaching other people too. Teaching herself to read braille gave her some of the tools she needed to teach others. Enwereji enjoys making games out of teaching, allowing the kids she teaches to enjoy the learning experience more. She believes that braille and other tools for visually impaired people should be as accessible as those for sighted people. That’s a focus of her social media outreach, @braillion on TikTok and Instagram. Enwereji is in her last semester of becoming certified to be a teacher of students with visual impairments (TVI).

“Braille is access and access equals opportunity. Literacy is a right in every form and everybody deserves the right to read. #braille”

Meet Judy Dixon

Judy Dixon learned braille in first grade. For her, she was just learning to read braille like sighted children learned to read print. When she got to high school and then college, she realized the value of braille when people told her she couldn’t get all of her books in braille. She realized that braille can be scarce and expensive.

After earning her Ph.D. in clinical psychology, Dixon has spent the last 41 years working for the Library of Congress. She has written 15 books for braille readers on topics such as labeling, photography, and audio description. In 2005 she won the Frances Joseph Campbell Award from the American Library Association. She was chair of the Braille Authority of North America, before becoming the president of the International Council on English Braille.

“If blind people want to keep braille, we have to fight for it.”

![Edward Bell, wearing a red button down shirt and holding his cane, is standing on the edge of a green lawn, with a southern style building on the Louisiana Tech College campus in the background.] Edward Bell, wearing a red button down shirt and holding his cane, is standing on the edge of a green lawn, with a southern style building on the Louisiana Tech College campus in the background.]](https://info.nbp.org/hubfs/Eddie-1.jpg)

Meet Edward Bell

Growing up poor, Eddie Bell had little hope for his future. With braille, he was able to continue his education and he never looked back. Bell is the director of the Professional Development and Research Institute on Blindness at Louisiana Tech University. Blind since the age of 17, Bell used braille to earn his GED, all the way up to his PhD. Focusing on rehabilitation education and research, educational psychology, and human development, Bell is also certified in educational statistics, research methods, rehabilitation counseling, and orientation mobility.

“If you think that braille is the key to literacy; that it is the path to literacy, freedom, independence, hope, success, satisfaction, and fulfillment, then it will be.”

Meet The Silvas

There are three braille readers in the Silva family. Matheus, 11, is blind; Benjamin, 9, has low vision; and their mother, Simone, learned to read braille as well. Matheus and Benjamin each started learning braille when they were three years old. They have a braille teacher who helps them learn together. They each read and write in braille, and sometimes they read books together. Both kids play piano, using their hearing to identify the keys. They enjoy playing soccer together, seeing who can score the most on five shots. Matheus can use a soccer ball with a bell inside that helps him hear where it is, but at home he often just uses one without a bell. Matheus also enjoys cooking and Benjamin enjoys jumping on the trampoline.

“Print/Braille books were very important when they’re very young, and they’re still very important. When they were babies, they started to learn braille just by touching the pages. They can grow with the books.” -Simone

Meet Kate Crohan

Kate Crohan was born without sight, but it wasn’t until she started school that she was introduced to braille. It was love at first touch. Crohan went to the Oak Hill School for the Blind growing up and wanted to be a teacher. Using braille, she made it happen. She taught at the Carroll Center in Newton for 10 years and has been teaching at the Perkins School since 2008. Her didactic fields include independent living, educational services, communication skills, and technology and braille.

“I fell in love with braille the moment I was exposed to it. Without braille, all these extra things in my life wouldn’t be possible: reading at church, recipes, knitting patterns, children’s books, card games, labeling.”

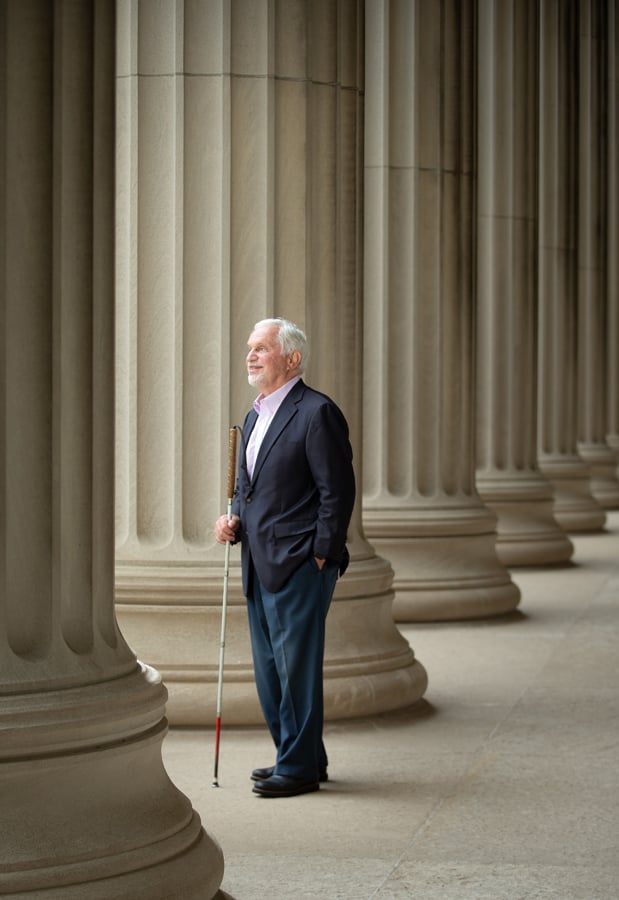

Meet Paul Parravano

Paul Parravano became blind at the age of three due to retinal cancer. His parents taught him braille, and it has made his work and education possible. Parravano is the co-director of Government and Community Relations at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Without braille, he couldn’t take notes or retrieve the information he needs to in order to do his job. Parravano’s local engagement includes scientific communities and disability rights communities, among other causes. An avid braille reader, he has served as a trustee of the National Braille press for almost two decades, and keeps up with the latest technologies for the blind and visually impaired.

“In my view, there is no substitute for braille, when maintaining a busy hectic calendar, or quickly and accurately accessing key pieces of data that I might need throughout the day. Whether for work, pleasure or family life, keeping braille close to me is critical for maximum independence and freedom.”

With the right tools, anything is possible. Give the gift of braille literacy to put blind children on the path to literacy and give them the tools they need to live their most successful lives.

Come back next week to meet a new Face of Braille!

Thank you so much to all of our participants for sharing your braille story! A special thank you to Roger Pellisier, who donated his photographic talent and creative direction to the project. It wouldn't have been possible without you all!